|

Authors Doug Blandy, Olivia Gude and Patricia Stuhr, see contemporary art education as a means to promote the ethical self-actualization of a student who is operative in a democratic society and classroom. Furthermore, the authors promote encouraging students to develop habits of inquiry. All the while participating in a material rich society as they explore relevant cultural and conceptual content in class and in life. Gude suggests that art education instills empathy and develops one’s imagination (Gude, 2009, p. 4). Quality art education also helps students define meaning in the arts and in life. These understandings are vital to functioning within a democratic environment. Gude furthermore states, “…education in the arts creates the capacity to see and sense the complexity of oneself. Arts education develops the capacity for nuanced and eloquent articulation of experience, for developing the methods by which self and shared meaning is made” (Gude, 2009, p. 3).

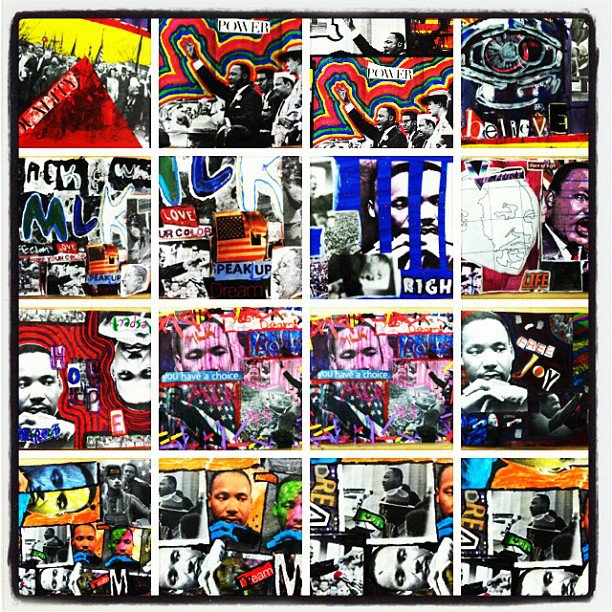

Blandy, Gude and Stuhr identify specific components that art education can use in the plight of staying relevant and meeting the developmental, social and intellectual needs of the student. Blandy includes the world’s need for sustainability as well as the participatory and materialistic nature of art and technology in experiencing, creating and analyzing artifacts (Blandy, 2011). Gude sticks closely with the inclusion of Lowenfeld ideologies that promote self-actualization through experience and exploration in art materials and subjects. Stuhr emphasizes the need for cultural relevance and like Lanier before her, does not avoid the inclusion of controversial subject matter as it relates to the student’s real life situations (Stuhr, 2003; Lanier, 1969). Just as each culture is different, so is each generation, campus and class. Of course commonalities exist among the human experience throughout, yet each specific classroom has unique needs, just like the individual student. I feel the challenges faced by the authors thus far are summarized like so; they approach universal ideas (empathy, wonder, inquiry and meaning) but do so using transitional cultural methods. The authors’ approaches are based on the cultural reserves of the moment. To me they are all worthy of exploration and in specific instances application. In general, a blending of the ideologies past and present as they are applicable may be a more complete approach. I see some individual and universal obstacles too. The major being systemization of our schools, increasingly in art curriculum maps, content and assessment standards. (Our county is implementing those next year). This leads to another major obstacle. Like in times past receptivity to new ideas is key. As Stuhr points out, no one listens (Stuhr, 2003), and more emphatically I maintain, no one understands. I seriously hope it isn’t that no one really cares. On that note, I think it is imperative to require training for administrators in arts pedagogy. How can one supervise and assesse when uninformed and unqualified themselves? I recently taught on the Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement for African American History Month. I teach in a very multicultural setting. Many of my students come from Puerto Rico, the Caribbean, South America, N.Y. or Miami. Many students are bilingual and some are the first in their family to speak English primarily. I used the thematic event to promote enduring ideas in transition with art creation. I was surprised at the great disconnect that my students had regarding some of the facts and issues and more importantly the relevance to their own freedoms. However, to note, some students had a more complete knowledge of the historical record. I wanted to show relevancy between issues of equality, non-violent protest, and the power of a collective voice. These intrinsic values held true as we explored the content applying principles to our classroom, campus and lives. We all gained new understanding throughout. We made three projects from the lesson: posters identifying key words relatable to our lives then and now, a puzzle pop art piece where each child produced a few squares that were integrated into an image of Dr. Martin Luther King and a personal collage exploring “repetition that creates rhythm in a piece of art work.” We used images from the civil rights movement and lettering to communicate personal understandings and expressions regarding the historical event. In all the wisdoms gained from other art educators and leaders, it is paramount, as is the thesis thread within these readings, to use art as a means in educating the individual for self-actualization, thriving development, success and survival in our pluralistic world. Doing so involves understanding culture, activating participation and responsibility within democratic processes. We operate individually and collectively in a democratic society that affords us opportunities for learning, understanding, harmony and tolerance. In this, we are good to offer and share ideas to develop this personal and collective growth, just like we should teach our students through art education. Blandy, D. (2011). Sustainability, participatory culture, and the performance of democracy: Ascendant sites of theory and practice in art education. Studies in Art Education, 52(3), 243-255. Lanier, V. (1969). The Teaching of Art as Social Revolution. The Phi Delta Kappan, 50(6), 314-319. Retrieved February 23, 2014, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20372341 Gude, O. (2009). Art education for democratic life [NAEA Lowenfeld Lecture]. Retrieved from http://www.arteducators.org/research/2009_LowenfeldLecture_OliviaGude.pdf Stuhr, P. L. (2003). A tale of why social and cultural content is often excluded from art education and why it should not be. Studies in Art Education, 44(4), 301-314.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

Scott HughesArt Educator, Professional Photographer, Journalist. Alumni: Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed