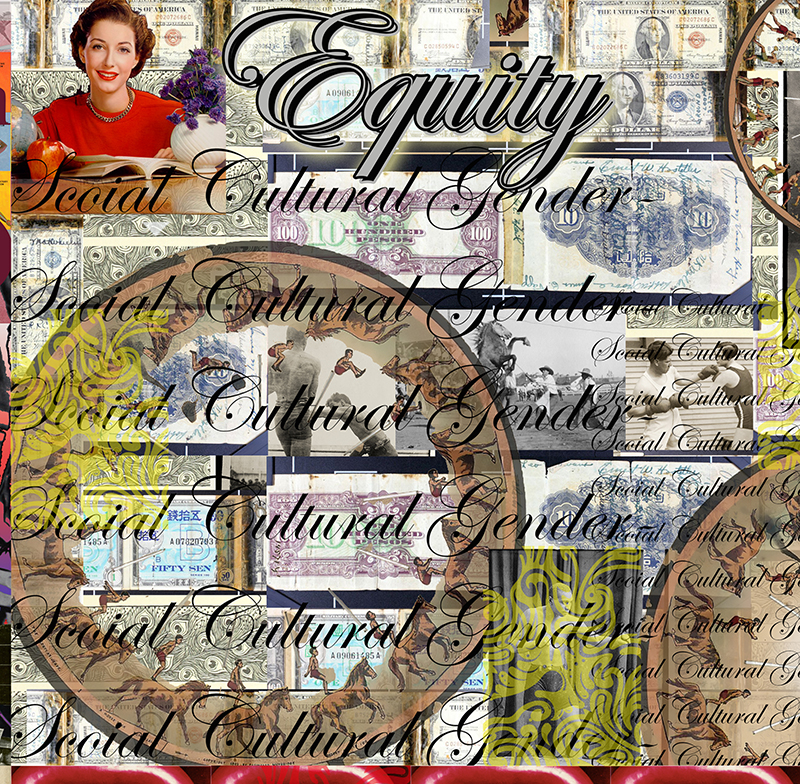

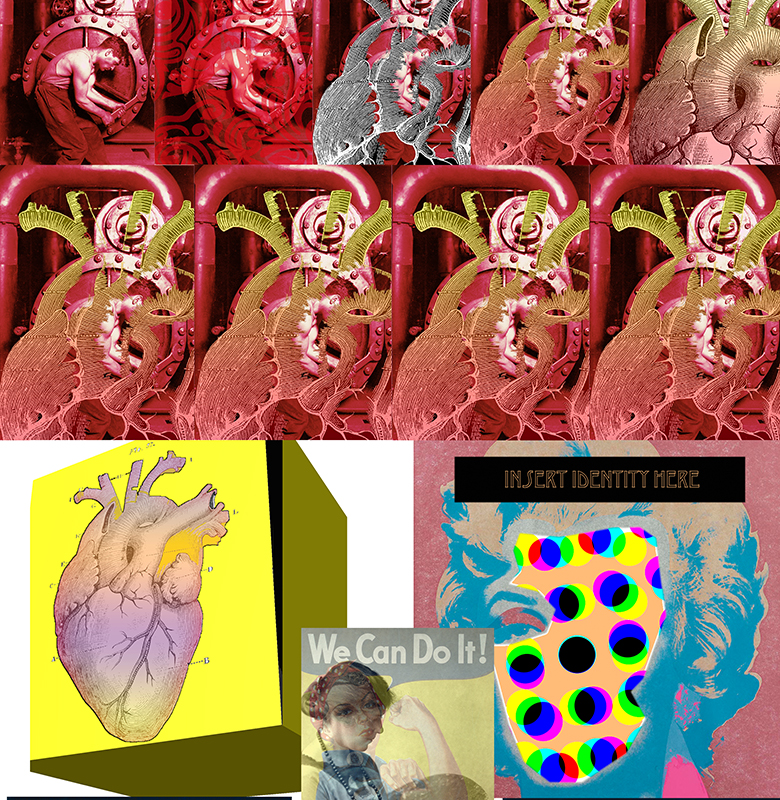

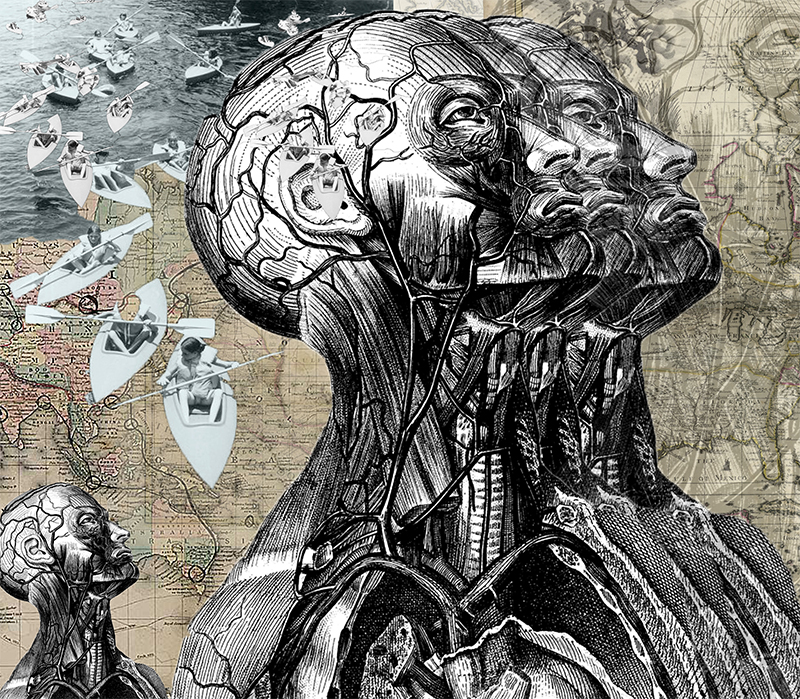

Same Thing, Different Way...The roles and responsibilities of an art educator are in constant flux. Twenty first century challenges have evolved. Some are congruent and some intersecting from our past. With that said, this artwork explores and expresses some of my concerns as an artist and art educator. Anytime we look to see, we are already perceiving something historic. Whether it be the twinkling stars at night, or the image reflected of a nearby friend on our retina. We are literally living in the past. Much can be learned here and it is the intent of this author to show with clarity some of the "same things" in a "different way" that have demonstrated prevalence for over the last 100 years. In learning from our past we may find better ways to live in future times. It is good to read the pulse of culture, to see the direction of humanity and get an idea of where we fit into the bigger picture. In the late 1800's emphasis was placed on art education to keep with up growing technologies. We see a similar push in today's emerging technology sector as well. As in yesteryears, social, economic, political and cultural factors still have major influence in societal living today. Recognizing and honoring human equity is of utmost importance in our treatment of others. Educators in the United States wage war daily against ignorance, striving for a community of responsible, educated individuals who will nurture and practice a free thinking, democratic way of life. This artwork is my reflective attempt to address those issues central to every human being. Those are matters not just of intellect, more so of the heart. How do we effectively reach those around us, promoting the arts and art education in a way that is transformative for all involved and a call to those who have no involvement or awareness therein? How can we as art educators define and fulfill the roles society has placed on us in our profession? "How" is not always a question easily answered, however, it is an endeavor we must not fail to pursue. Details:21st Century Art Educator Roles Imagine

Imagine we have silently dropped down into the back of a middle school art classroom. As we observe, the projector screen lights up with examples of the high tech and innovative work of Fabian Oefner, Reuben Margolin and Theo Jansen. Oefner’s high definition photographs explore creative perspectives on the properties of matter. Fiber optics made to look like telescopic images of space, spinning splashes of paint with vibrant colors are captured in an instant. The usually unseen world of soap bubbles bursting and sound waves sculpting form displayed throughout (TEDGlobal 2013). Margolin’s repurposed materials are formed into water eddies while his mechanized caterpillars demonstrate a keen ability to relate to natural phenomena (Make Magazine, 2009). Students intently view Jansen’s larger than life, wind driven sculptures as they walk seaside beaches. Anomalies they are, with joints bending and stepping, they resemble fossilized ancient creatures or spindly futuristic robots (Theo Jansen, n.d.). We would most likely hear the shifty and vocal excitement of students being exposed to such artwork for the first time. To look around we would see the eyes of youngsters fixed on the screen with faces of interpretation, wonder and concentrated engagement. Such has been the case in my own art classroom. In art education we possess a unique wonder to share with others. The act of creation alone provides numerous opportunities for exploration and learning. The experiential insights of working with materials and mediums’ behaviors, limitations and adaptations are enormously valuable. This is so of its own merit and within the correlations of cross disciplines and domains. The conceptual and historical studies in art education prove to be substantial in scholarship. Meaning is constructed from personal and collective experience and art offers a way to democratize pluralistic content and the populous. Culturally studying the arts help us to understand various sensitivities. We ask why? With such an experience waiting for eager students to enter in, it is a curiosity as to why some educational leaders and administrators don’t better understand all the value the arts offer. It is further perplexing as to why curriculum freedom is increasingly restricted within the art classrooms. Exemplifying how creative energies can be dynamically manifested are the examples of the aforementioned artists. Additionally for instance, is the broad intellectual power of collaborative venues like TED Talks. Why is it then that schools currently lack provision in fluid, technologically relevant, professionally collaborative approaches to learning? More so, evidence suggests open-ended explorations bring motivated discovery and develop the habits of a creative individual (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). Diverse platform symposiums provide cutting edge inspiration and a proliferation of profound ideas. These brief reflections of real world life integrate within arts collective pièce de résistance. Shouldn’t we then follow these examples on campuses and specifically in art education? If John Dewey was centered on students leaving classroom experience equipped for productive societal life experience (Harris & Neiman, n.d.) we should all the more support art educators’ roles in facilitating this diverse and higher ordered learning. However, reality demonstrates little wiggle room for art educators. Classes are ill provided with outdated and “over filtered” technology, large class sizes make teaching impractical and in some cases unreceptive administrators are uneducated to the many avenues fitting art educational practice. This only further marginalizes our profession. Worse, art education may be morphed into a social studies template, or an academically based humanities component. Art education leader Vincent Lanier was overt in pushing a validation of art education through refined analysis and critique in practice. Using the mass media of his day, (i.e. primarily film), and covering various forms of visual culture, Lanier prodded down a path hopeful students would find deeper meaning and eventually analyze finer art (Lanier, 1966). His promotion of avoiding and even abandoning studio practice was in theory a fire that may burn brighter in future education circles. However, like John Ruskin most artist/art educators understand the value of working with ones hands, head and heart in creating and understanding art (Ruskin, 1859, p. 54). Contrastingly, due to the attractions of digital media, strains on school budgets, and students’ lack of early educational arts training, traditional studio methods of art creation (in many cases) are becoming more challenging to implement. Digital Influence With youth culture we see this obvious gravitation to the digital. Like no other generation before has access to personal, powerful technology brought the Internet and software applications into the palm of our hands. Mobile and massive, students can see more, do more and experience more than ever before. Yet as noted by Gilbert Valdez, students in the classroom perceive poor teacher knowledge, preparedness and pedagogical skills regarding classroom technology (Valdez, 2005, p. 4). This contributes to the “disconnect” in harnessing that same power for deep classroom instruction. In this sense, maximum effectiveness using technology should be our aim. It is the responsibility of the art educator to be proficient in such matters and imperative if these new measures are going to be successfully utilized (p. 4). Problems stemming from the ongoing recession in America have fueled hindrances in public education’s ability to keep up with industry and in some cases the proverbial Joneses (i.e. other countries where contemporary technology provision in schools is an emphasized priority) (Zakaria, 2011). Our students require “unique ways of acquiring and interpreting knowledge” (Tillander, 2008, p. 232). Opportunity through skilled pedagogical use of new technology will be key. In general, students need valuable art experiences to help develop their full personal potential (Jeanneret, 2008). If schools systems do not keep current, art education will be greatly affected, falling off the studio slope and wiping out on the wave of progress. For students to succeed in the next five to ten years, technology provision in school reform will have to take precedence and start immediately. If not, provision from private industry and developers of application freeware will have to make considerable contributions to supplement. In the case of free applications, usefulness is limited. Developers’ ventures become money making opportunities and the product is sometimes reduced, abandoned or becomes outdated. Bright spots do persist as in the case of Google’s Sketchup and the web based image editor, Pixlr, absorbed into larger companies, yet still available for free (Bacus, 2012; Wauters, 2011). There may need to be more powerful open source contributions from founders like Edutopia, EdTech and the Kennedy Center for the Arts, including wealthy museums to provide high-end applications for the 21st century art classroom. Could this be a new direction for museum education? This idea in technology provision may be an additive to the current push for what I call “hubbing.” The NAEA put forth research agenda promoting scholarly collections be centralized and accessible (NAEA, n.d.). Upon my own explorations I was surprised to see sites like Edutopia and The Warhol already amassing collections of scholarly articles through annotated bibliographies and active links (Vega, 2014; The Warhol, n.d.). Will agencies like these be able to facilitate the development of substantial classroom technologies overall? Researchers and educators active in advocacy and leadership will surely benefit from the strides already made in establishing collective repositories, another example of using technology effectively in professional development. Cultural Meaning and Investment Using a comprehensive approach, art education helps students find deeper meaning from critiquing and analyzing works of art while exploring periods of history and artists biographies. (University of North Texas, n.d.). Art educators must present relevant material and be educated themselves as to the complexities that exists within cultural crossings. As Bastos (2006) and Coulby (2006) suggest these intersections can be challenging, require research and implore us to get directly involved with participants, increasing cultural understanding, sensitivity and overall growth. Art educators will be instrumental in promoting social and cultural equity as in times past. With activism it will be the role of the educator to help students find the means to influence their community. Professionally art teachers will raise voices to solidify art education’s value. Activism will be essential in promoting the continued existence of art education on campuses while instilling the value of art education throughout future generations. Educators will need to ensure that students receive investment from their place in time. Many students in my experience were not born where they now reside. This transplantation and cultural exchange often leaves a shallow experience as to the roots and history of their surroundings. Without knowledge of these histories, socially and geographically, little value is placed on their environment. It is reflective on campus and in their integrated personal identity. To know about the unique natural features, resources and benefits of one’s neighborhood, community, region and state are enriching. It is essential for human beings to have a sense of belonging in local community. Focused on these attributes, art education can strengthen bonds and connectivity long term. In a pluralistic society this can create new heritage, just like creative studies help to produce new knowledge, domain changing in some cases (Milbrandt, 2011). In this role the art educator will be a storyteller of sorts, handing down historical significance and identifying locational resources for the student. The art educator can help raise awareness of their unique place in the world, promoting a sense of involvement, belonging, enjoyment and worth. In bringing meaning to art, place and history, it is also essential for art educators to encourage finding meaning in the myriad of visual culture that surrounds us. With growing access to imagery, memes, remixes and the like, students sometimes lack grounding and discernment to navigate effectively the messages they encounter. The role of the art educator will require us to engage in popular culture so that we can help in decoding information. Art teachers must guide students as they decipher negative influences and the prevalent cynicism found in many pop culture artifacts. Some images first appear humorous, however, upon analysis expose damaging input beyond the surface. Adult created imagery, yet with juvenile styling, can send mixed messages regarding life experience, empathy and cultural sensitivity. Although some popular media is inherently useful and intrinsic, it is the access to derivatives and disparate concepts that stand in contrast to responsible democratic citizenship. These subjects need a knowledgeable teacher, facilitating transition to teachable moments of redirection that are useful for personal and collective growth. Learning in the end Evidence supports that contemporary, fluidly diverse, collaborative and culturally responsible methods should be developed and applied to art education. The National Research Council states, “Knowledge that is taught in a variety of contexts is more likely to support flexible transfer than knowledge that is taught in a single context,” (The National Research Council, 2000, p. 236). Of course art educators are accustomed to wearing many hats. However, the role of the 21st century art educator is not just to teach in context and content. The art educator should instead, teach to learn alongside their students. The goal is to build habits of inquiry that lead to discovery and growth (Wiggins, 1989). When we do so, the aim is not the various practices. Instead the aim is to incorporate the positive and transformative power art education has on the human mind, heart and hand. Especially in our students and ourselves. References: Bacus, J. (2012, April 26). Official SketchUp Blog: A new home for SketchUp. Retrieved from http://sketchupdate.blogspot.com/2012/04/new-home-for-sketchup.html Bastos, F. M. C. (2006). Border-crossing dialogues: Engaging art education students in cultural research. Art Education, 59(4), 20-24. Coulby, D. (2006). Intercultural education: theory and practice. Intercultural Education, 17(3), 245-257. Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Sussex Publishers LLC. (1996, July 1). The Creative Personality. Retrieved April 13, 2014, from http://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/199607/the-creative-personality Harris, S., & Neiman, D. (2000). PBS online: Only a teacher schoolhouse pioneers. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/onlyateacher/john.html Jeanneret, D., & NSW Public Schools. (2008, November 13). Developing children's full potential: Why the arts are important. Retrieved from http://www.schools.nsw.edu.au/learning/k_6/arts/kids_potential.php Lanier, V. (1966). Newer Media and the Teaching of Art. Art Education, 19(4), 4-8. Retrieved February 21, 2014, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3190788 Make Magazine. (2009, January 29). Maker Profile - Kinetic Wave Sculptures on MAKE: Television. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dehXioMIKg0 Milbrandt, M., & Milbrandt, L. (2011). Creativity: What Are We Talking About?. Art Education, 64(1), 8-13. NAEA. (n.d.). Creating a visual arts education research agenda for the 21st century: Encouraging individual and collaborative research (Rep.). Retrieved April 7, 2014, from NAEA website: http://www.arteducators.org/research/NAEA_Research_Agenda_12-08.pdf National research council. (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=9853 Ruskin, J. (1889). The unity of art. In The two paths: Being lectures on art, and its application to decoration and manufacture (p. 54). New York, N.Y.: John Wiley & Sons. TEDGlobal 2013. (n.d.). Fabian Oefner: Psychedelic science. Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/fabian_oefner_psychedelic_science The Warhol. (n.d.). Unit Lesson Plans. Retrieved from http://edu.warhol.org/bibliog.html Theo Jansen. (n.d.). Beast photos events theo jansen miniature beasts | books | dvd contact. Retrieved from http://www.strandbeest.com/ Tillander, M. D. (2008). Cultural Interface as an Approach to New Media Art Education. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=EGu4J5jRqEAC&pg=PA232&lpg=PA232&dq=lack+of+technology+in+art+education&source=bl&ots=Rg8U32gkwn&sig=M1BxmLCKUwdJZdqPl-c3IJdablQ&hl=en&sa=X&ei=rMlaU6mvBKrNsASusIHYBg&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=lack%20of%20technology%20in%20art%20education&f=false University of North Texas. (n.d.). North Texas Institute For Educators On The Visual Arts. Retrieved from http://art.unt.edu/ntieva/pages/teaching/tea_comp.html Valdez, G. (n.d.). Technology: A Catalyst for Teaching and Learning in the Classroom. Retrieved from http://www.ncrel.org/sdrs/areas/issues/methods/technlgy/te600.htm Vega, V. (12, December 12). Technology integration research review: Annotated bibliography. Retrieved from http://www.edutopia.org/technology-integration-research-annotated-bibliography Wauters, R. (2011, July 19). Autodesk Acquires Online Photo Editing Service Pixlr TechCrunch. Retrieved from http://techcrunch.com/2011/07/19/autodesk-acquires-online-photo-editing-service-pixlr/ Wiggins, G. (1989). The futility of trying to teach everything of importance. Educational Leadership, 44-59. Zakaria, F. (2011, March 03). Are America's Best Days Behind Us? Retrieved from http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0%2C9171%2C2056723%2C00.html

3 Comments

|

Scott HughesArt Educator, Professional Photographer, Journalist. Alumni: Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed