|

In the article, Children Never Were What They Were: Perspectives on Childhood, Paul Duncum compares the facts of historical and contemporary notions of childhood innocence and development, to the reality of childhood states and conditions. This is evident within his account of children’s lives throughout history and his idea that perceived innocence is a nostalgic reference we adhere to as adults in order to preserve and even protect our own inner child and children in general (Duncum, 2002). He posits we subsequently exaggerate the true state of child innocence.

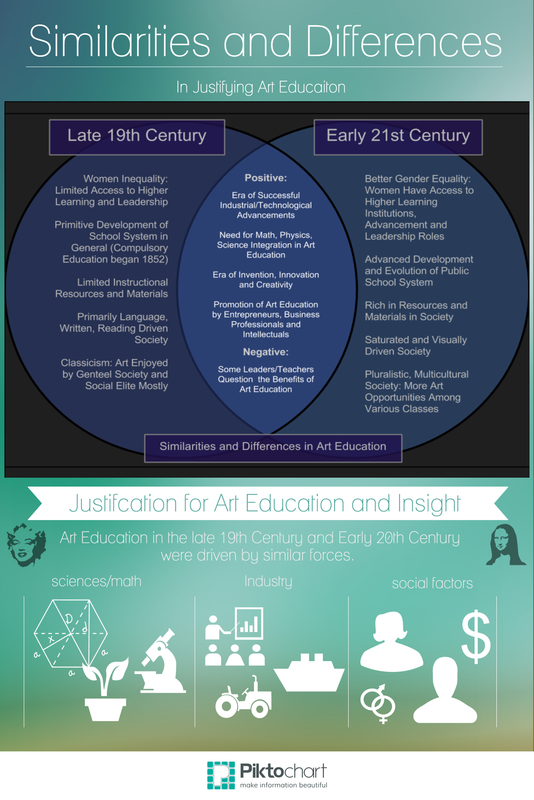

Factually, history has afforded us a glimpse into the lives and treatment of children. The reality is more centered on systems adults have built and in some cases used to exploit and integrate children into society. Specifically, as in the American Industrial Revolution, children worked along side adults and in their stead, only to have the artist and photographer Lewis Hine spearhead efforts to eliminate unfair child labor practices. The real issue for me is the systems adults in humankind often develop that force children into an earlier maturation that is unhealthy or hinders optimum growth and thriving development. Oftentimes, children are conditioned through elements, insensitivity and/or corruption fostered in the adult arena. I also see that through exposure and experience, kids just seem to lose the ideologies of innocence. The sense of wonder and awe were there, however, they dissipate, sometimes perhaps because of corruption through experiential means. They experience the life that adults produce, through products geared at kids and general products they have access to. In the worst of scenarios children suffer indignities at the hands of adults and other children. As an educator, I believe it is paramount that I approach children in a realistic way. Acknowledging that they have experiences that are painful, real and substantial, just like adults. In some cases living around contemporary pop culture that is heavily saturated with media and entertainment sources can be harmful. Sources like these can speed up a child’s awareness and maturation beyond their developmental years. They may not be equipped to navigate clearly with reason and rationale those experiences and impressions. The inability of understanding and in dealing with these issues for children are not driven by “falsetto” innocence, these inadequacies are fueled by their innocence lost. To me, my job is to meet the child’s educational, developmental, emotional and social needs through professional practice. I don’t concretely mandate that they should achieve a certain level of maturation or even artistic skill by a certain age or grade level. They are organic individuals developing uniquely. To note, even Einstein was not well respected by teachers and peers early on in his college and professional life. For me, I am an encourager, a protector, a cheerleader, a mentor and someone who invests their time into the child, teaching them to invest time into themselves. The discoveries in art and the integration of the curriculum are really superseded by the need of the child to develop in a healthy way. My goal is to help this by being personable, professional and as Dr. Martin Luther King said, valued on the content of my character. I say that living in the classroom is essential, teaching art is peripheral. When we look at children as valuable people, then the bridge to learning can begin. I offer a sympathetic ear to students and their life experiences. I try to be positive, letting them make their own decisions and I encourage them to see life as an opportunity, though with realistic challenges. I also point them to look at existence through the artistic lens educationally and relatively. If dealing with a, behavioral, moral or integral life issue, I try and help them make positive decisions that demonstrate respect for themselves and others, while keeping their freedom of choice. I use comedy as a means for living and teaching and even point out the purpose of doing so. Doing this may offer strategies to cope and enjoy moments in this life. I try to be realistic, they know I make mistakes, and they know as a human being I can understand the commonalities of frustration, failure, pain, joy, success and life. This helps them to know I am a real person and we share similar experiences and emotions. I practice empathy and hope that they will develop ways to do so too. To do this goes well beyond art instruction and really defines me as a teacher and a member of our campus community and a human being. Duncum, P. (2002). Children never were what they were: Perspectives on childhood. In Contemporary issues in art education (pp. 97-107). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. This infographic and post are from a recent entry in the discussion forum for the: History of Teaching Art with Dr. Roland! University of Florida "Just as there were various rationales proposed for art education in nineteenth-century American schools, there are many current popular justifications for art education in our nation’s schools. What similarities and differences do you see in the ways art education’s place in schools has been justified in the two eras (late nineteenth-century and early twenty-first-century America) What insights can be gained by examining the various reasons for justifying art education place in the school curriculum?" The Basic Need

In the late 19th century and early 21st century similar justifications exist for the inclusion of art education in the school system. In both centuries, because of the driving force of science, technology and industry, drawing and art education was and is essential in helping Americans keep up with developing technological and industrial advancements worldwide. Drawing and art education provide people with essential skills that can be applied to other professions. Students gain insight in enhanced observation and motor skill technique and improve their understanding of physics, engineering concepts and visualization. Developing eye hand coordination through artistic practice is beneficial in many areas of life. The enriching qualities of learning drawing and art help individuals open up understanding about life around them and discover applications for solving real world problems. In the 19th century, Walter Smith saw the importance of art for industrial growth and a skilled labor force in America (Stankiewicz, 2001). Like other affluent societal leaders, entrepreneur Louis Prang saw art as a way to improve upon societies’ understanding of artistic practice and appreciation. In addition to wanting more American skilled workers employed in his lithography business, Prang also looked towards a future of procuring sales from more educated art connoisseurs (Stankiewicz, 2001, p. 15). Still others in psychology and science saw the enriching qualities of art, promoting art education as a way to better see the world around us, express our inner thoughts and in some cases experience God’s creation more intimately through keen observation (Stankiewicz, 2001). Also in the 19th century, women played an important role in developing art education practices, however, they were granted limited access in, leadership, the workforce and in higher educational institutions. Although issues of classicism in general and discrimination against women predominated, pioneers like Mary Ann Dwight, Emma Willard and Mary Dana Hicks Prang persevered in laying foundational work while introducing and promoting art education within the schools (Stankiewicz, 2001). The developments regarding industry and society in both centuries offer very distinct similarities. The justification for art in schools was driven by science, industry, psychological and even natural or agricultural fields of study. One major difference evident in the late 19th century is that art for art sake had yet to come of age in the school system. Currently we are experiencing a new era of innovation, one that may be unprecedented before in history. This renaissance is more integrated and inclusive. We see justifications for art in schools as in times past. Most based on the needs and collective works between artists and highly skilled professionals. However, the lines that separate artists from other fields of study are becoming more blurred along the way. This resurging need for art education is due to evolved understandings about life, advancements in industry, technology, innovation, creativity and science. In much the same way as the late 19th century, art is helping progress. However, this time art, society and industry are driving towards a more high tech, virtual and digital lifestyle. Early 21st century agencies like Ted Talks and educational institutions like M.I.T. promote art’s integration into other areas of living and profession. Steve Jobs decidedly made design and function two of the most important facets of Apple products, both essential in art creation and engineering. Socially our world is much different, we have become centered on imagery, visually driven and society is more humanistic in nature. Art education has continued to offer enriching qualities of experience then and now. This time around, art education is more readily available and with the image saturated world we live in. Art has much more presence in our everyday lives than in centuries past. Overall, art education has been and is driven by need; however, I propose that art itself is an essential need in all of us. We play, we arrange and we create. We look to see and we learn to draw. We experience the wonder of nature and the wonder of creation, by God and by man. In all of this, art education plays a major role. It is true in our advancements as a society, as individuals, educators and as artists. Stankiewicz, M. A. (2001). Roots of art education practice. Worcester, MA: Davis Publications. |

Scott HughesArt Educator, Professional Photographer, Journalist. Alumni: Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed