A Review on Olivia Gude, Doug Blandy and Patricia Stuhr Art education has evolved to bring significant meaning to students through content and practice. Doing so validates art in the school curriculum. Authors Olivia Gude, Doug Blandy and Patricia Stuhr have all proposed pedagogies that offer meaningful experiences for students in the art classroom and validation of art educational practice on campuses throughout. By participating with material culture, exploring thematic content, and dealing with relevant ideas and problems, the authors deliver specific approaches that will contribute to the individual reaching their full potential. Their aims are to help the student define meaning individually and collectively, able to responsibly function within a democratic environment.

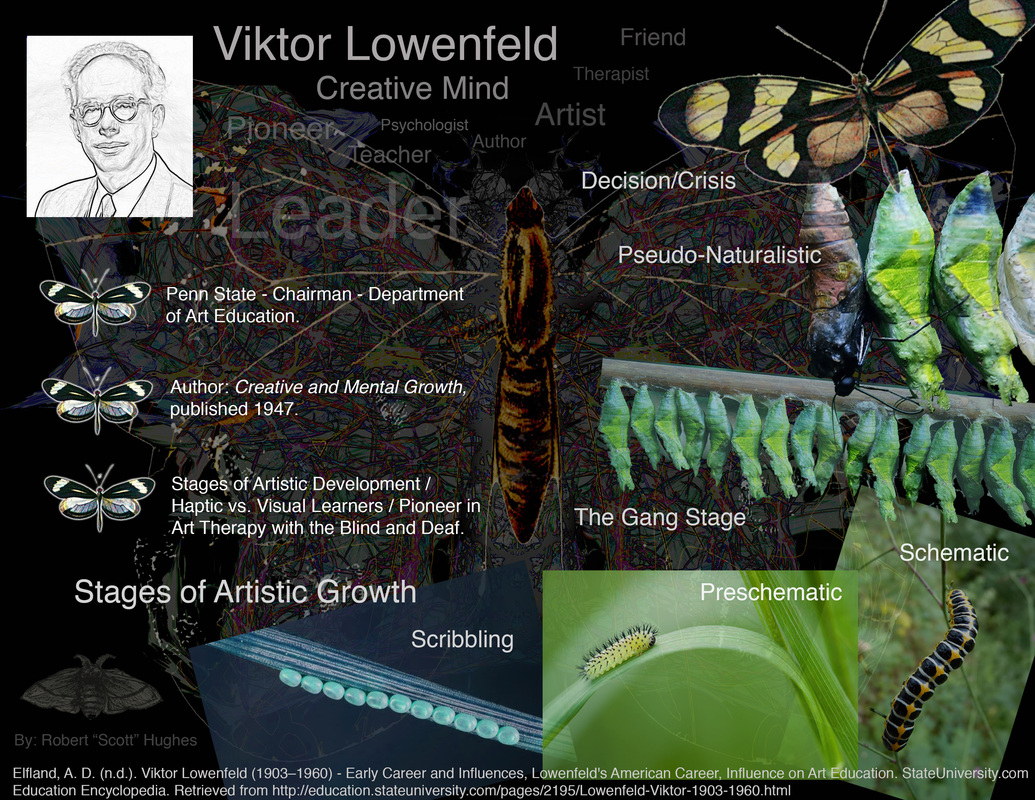

For Gude the focus tends to rely on Lowenfeldian approaches in educational practice. Engaging in quality art education, students create, “…the capacity to see and sense the complexity of oneself. Arts education develops the capacity for nuanced and eloquent articulation of experience, for developing the methods by which self and shared meaning is made” (Gude, 2009, p. 3). She concludes that in becoming art educated and artistically self actualized, one is able to develop empathy towards various worldviews and perspectives while activating personal meaning and a creative imagination (Gude, 2009). Blandy specifies a threefold approach utilizing the participatory nature of art materials, themes of sustainability and the performance of art education within a democratic model. With cultural movements in digital media, individuals are no longer required to possess formal accolades or degrees to be qualified as an expert in proficiency or artistry. Age is of little significance and one’s followers dependent upon reputation and formation through interest and connectivity with the artists work. In these networks, “Free Agent Learners” gain experience and knowledge using digital media daily in and outside of the classroom (Blandy, 2011, p. 249). In organizing the Digital Media and Learning Conference, 2010, Henry Jenkins aided studies into the behavior of people ages 13-28 engaged with technology. Blandy states, “Because there is a close relationship between participatory culture and immersion in digital media and social networking through electronic forums, he (Jenkins) often focuses on children and youth because of their facility with technology” (p. 249). Digital formats beckon engagement. Younger generations are naturally proficient in these modes of creation, dissemination and exploration. Understanding new swings in youth culture are valuable to integrating relevant meaningful content into the classroom. Stuhr focuses on the important cultural themes also relevant to student’s lives. Her goal is developing “social justice” and a subsequent understanding of the world for the student (Stuhr, 2003, p. 303). Emphasizing pertinent issues, controversial topics and exploring challenging ideas, like her predecessor, Art Educator Vincent Lanier, Stuhr sees art education as a means of social influence (Lanier, 1969). Stuhr supports empowering students to articulate and even tool art with cultural themes to infuse meaning and bring about changes in one’s thinking. “Art education, like all subjects, should be connected intimately to students' lives; therefore, curriculum, because of this connection to student life and their worlds, should be thought of as an ongoing process and not a product” (p. 303). Stuhr highlights the process of learning as of greater importance than the artifacts produced. Terms/Key Concepts Blandy introduces sustainability as beneficial for art exploration. Sustainability primarily deals with “place” and has influence on our population’s perceptions, activity and the function of art in society. Including cultural, social and environmental themes, sustainability explores shared identity, fosters understanding human imprints, ways of life and artifacts. Blandy aims to create responsible citizens engaged in preserving, honoring and changing their surroundings for the betterment of all, concepts vital to a democratic society. In quality art education students experience a dual mode of awareness and understanding (Gude, 2009, p. 1). Gude identifies that students engage in using their inner perceptions coupled with promptings from the outer world. For example, in looking at clouds or inkblots and using their imagination to envision alterations from the actual form, a student becomes integrated with the artistic process. Gude explains, “This is neither a journey to an isolated inner self nor an out-of-this-world trip, but the developed capacity to be aware of a self process through which one vividly notices and interacts with a world of objects and ideas” (Gude, 2009, p. 1). Gude further employs the importance of empathy, the act of relating to another’s experience and understanding the varying and often different viewpoints of others. In forming our own opinions, they may differ or coincide with another’s. Empathetic understanding is essential to the democratic process. Gude states, “…to be a truly democratic society we must persist in our individual and collective investigations of possibility; we must remain committed to thoughtfully engaging each other in our endeavors to make meaning and to make meaningful lives together“ (Gude, 2009, p. 5). Stuhr ultimately aims for an individual who appreciates and understands cultural diversity. To Stuhr, culture study provides values, explores patterns and beliefs that bring meaning to a person and life’s ever-changing dynamics (Stuhr, 2003, p. 303). Culture and curriculum should be integrated and modeled for students as it will “...enable them to enjoy life and prepare them to be independent, yet socially responsible individuals and informed and critical citizens” (p. 304). Imperative are individuals who actively participate in a world where social justice is realized. Social justice is achieved when the individual reaches their full potential in human practice and honoring the collective and individual worth of a pluralistic society. Sturh believes this is done by, “…the investigation of social and cultural issues from multiple personal, local, national, and global perspectives” (p. 303). Critical Response/Application/Personal Reflection In exploring cultural themes, I would like to teach on a selfie project. I would like to see the students investigate the standardization of beauty, identity and self-image within a contemporary cultural context. I would challenge the students to explore the reality of human vulnerabilities and insecurities in being the author and subject of an image. Students could reconcile perceptions with the need for empathetic understanding of others and acceptance of self. Students would explore what culture says about beauty and identity as opposed to our natural and deeper personas. I would challenge students to consider rethinking their personal stances on world standards of aesthetics, beauty and identity stereotypes and our attitudes towards others of a different physical, cultural or social make up. Students would explore the use of apparel and how identifiers are formed because of represented fashion choices. Lastly, my students could uncover commonalities that we all face as individuals in society that lead to looking at people with discrimination, rejection, bullying, favorability, popularity and acceptance, producer and recipient. I would reference Dawoud Bey’s Class Picture series (Bey, 2007) and the Dove Selfie Project (Dove United States, 2014) for motivations, inspiration and modifications. Challenges include, provision of adequate technology, overcrowded classes, and some students being uncomfortable in self-portrayal or exhibition of self-imagery. I would seek the use of personal cell phone photography, shared technology among peers, allowing students to produce image ideas at home, (not limited to the classroom) and encourage engagement by modifying the assignment if needed and using inspirational sources (portrait of another person and/or inspiration from aforementioned sources). References Bey, D. (2008). Class Pictures: Photographs by Dawoud Bey. Milwaukee Art Museum. Retrieved March 9, 2014, from http://mam.org/bey/gallery.htm Blandy, D. (2011). Sustainability, participatory culture, and the performance of democracy: Ascendant sites of theory and practice in art education. Studies in Art Education, 52(3), 243-255. Retrieved from http://www.arteducators.org/research/studies Dove United States. (2014, January 19). Selfie. YouTube. Retrieved 2014, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BFkm1Hg4dTI Gude, O. (2009). Art education for democratic life. Paper presented at the NAEA Lowenfeld Lecture, . Retrieved from www.arteducators.org/research/2009_LowenfeldLecture_OliviaGude.pdf Lanier, V. (1969). The Teaching of Art as Social Revolution. The Phi Delta Kappan, 50(6), 314-319. Retrieved February 23, 2014, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20372341 Stuhr, P. L. (2003). A tale of why social and cultural content is often excluded from art education: And why it should not be. Studies in Art Education, 44(4), 301-314. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1321019

5 Comments

Authors Doug Blandy, Olivia Gude and Patricia Stuhr, see contemporary art education as a means to promote the ethical self-actualization of a student who is operative in a democratic society and classroom. Furthermore, the authors promote encouraging students to develop habits of inquiry. All the while participating in a material rich society as they explore relevant cultural and conceptual content in class and in life. Gude suggests that art education instills empathy and develops one’s imagination (Gude, 2009, p. 4). Quality art education also helps students define meaning in the arts and in life. These understandings are vital to functioning within a democratic environment. Gude furthermore states, “…education in the arts creates the capacity to see and sense the complexity of oneself. Arts education develops the capacity for nuanced and eloquent articulation of experience, for developing the methods by which self and shared meaning is made” (Gude, 2009, p. 3).

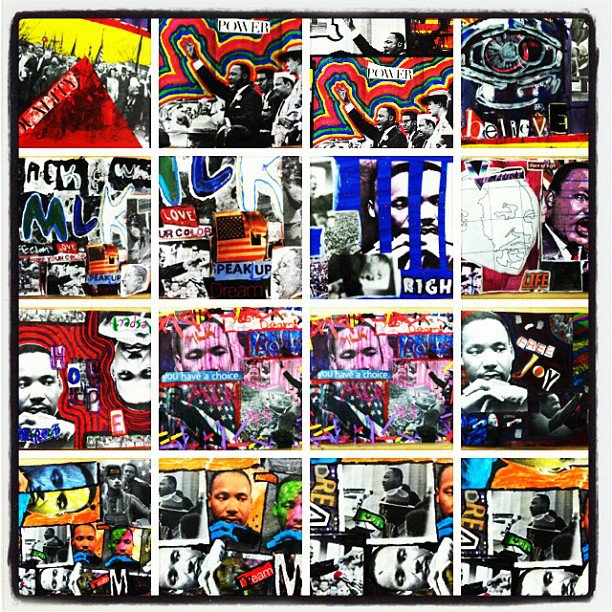

Blandy, Gude and Stuhr identify specific components that art education can use in the plight of staying relevant and meeting the developmental, social and intellectual needs of the student. Blandy includes the world’s need for sustainability as well as the participatory and materialistic nature of art and technology in experiencing, creating and analyzing artifacts (Blandy, 2011). Gude sticks closely with the inclusion of Lowenfeld ideologies that promote self-actualization through experience and exploration in art materials and subjects. Stuhr emphasizes the need for cultural relevance and like Lanier before her, does not avoid the inclusion of controversial subject matter as it relates to the student’s real life situations (Stuhr, 2003; Lanier, 1969). Just as each culture is different, so is each generation, campus and class. Of course commonalities exist among the human experience throughout, yet each specific classroom has unique needs, just like the individual student. I feel the challenges faced by the authors thus far are summarized like so; they approach universal ideas (empathy, wonder, inquiry and meaning) but do so using transitional cultural methods. The authors’ approaches are based on the cultural reserves of the moment. To me they are all worthy of exploration and in specific instances application. In general, a blending of the ideologies past and present as they are applicable may be a more complete approach. I see some individual and universal obstacles too. The major being systemization of our schools, increasingly in art curriculum maps, content and assessment standards. (Our county is implementing those next year). This leads to another major obstacle. Like in times past receptivity to new ideas is key. As Stuhr points out, no one listens (Stuhr, 2003), and more emphatically I maintain, no one understands. I seriously hope it isn’t that no one really cares. On that note, I think it is imperative to require training for administrators in arts pedagogy. How can one supervise and assesse when uninformed and unqualified themselves? I recently taught on the Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement for African American History Month. I teach in a very multicultural setting. Many of my students come from Puerto Rico, the Caribbean, South America, N.Y. or Miami. Many students are bilingual and some are the first in their family to speak English primarily. I used the thematic event to promote enduring ideas in transition with art creation. I was surprised at the great disconnect that my students had regarding some of the facts and issues and more importantly the relevance to their own freedoms. However, to note, some students had a more complete knowledge of the historical record. I wanted to show relevancy between issues of equality, non-violent protest, and the power of a collective voice. These intrinsic values held true as we explored the content applying principles to our classroom, campus and lives. We all gained new understanding throughout. We made three projects from the lesson: posters identifying key words relatable to our lives then and now, a puzzle pop art piece where each child produced a few squares that were integrated into an image of Dr. Martin Luther King and a personal collage exploring “repetition that creates rhythm in a piece of art work.” We used images from the civil rights movement and lettering to communicate personal understandings and expressions regarding the historical event. In all the wisdoms gained from other art educators and leaders, it is paramount, as is the thesis thread within these readings, to use art as a means in educating the individual for self-actualization, thriving development, success and survival in our pluralistic world. Doing so involves understanding culture, activating participation and responsibility within democratic processes. We operate individually and collectively in a democratic society that affords us opportunities for learning, understanding, harmony and tolerance. In this, we are good to offer and share ideas to develop this personal and collective growth, just like we should teach our students through art education. Blandy, D. (2011). Sustainability, participatory culture, and the performance of democracy: Ascendant sites of theory and practice in art education. Studies in Art Education, 52(3), 243-255. Lanier, V. (1969). The Teaching of Art as Social Revolution. The Phi Delta Kappan, 50(6), 314-319. Retrieved February 23, 2014, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20372341 Gude, O. (2009). Art education for democratic life [NAEA Lowenfeld Lecture]. Retrieved from http://www.arteducators.org/research/2009_LowenfeldLecture_OliviaGude.pdf Stuhr, P. L. (2003). A tale of why social and cultural content is often excluded from art education and why it should not be. Studies in Art Education, 44(4), 301-314. In the article, Children Never Were What They Were: Perspectives on Childhood, Paul Duncum compares the facts of historical and contemporary notions of childhood innocence and development, to the reality of childhood states and conditions. This is evident within his account of children’s lives throughout history and his idea that perceived innocence is a nostalgic reference we adhere to as adults in order to preserve and even protect our own inner child and children in general (Duncum, 2002). He posits we subsequently exaggerate the true state of child innocence.

Factually, history has afforded us a glimpse into the lives and treatment of children. The reality is more centered on systems adults have built and in some cases used to exploit and integrate children into society. Specifically, as in the American Industrial Revolution, children worked along side adults and in their stead, only to have the artist and photographer Lewis Hine spearhead efforts to eliminate unfair child labor practices. The real issue for me is the systems adults in humankind often develop that force children into an earlier maturation that is unhealthy or hinders optimum growth and thriving development. Oftentimes, children are conditioned through elements, insensitivity and/or corruption fostered in the adult arena. I also see that through exposure and experience, kids just seem to lose the ideologies of innocence. The sense of wonder and awe were there, however, they dissipate, sometimes perhaps because of corruption through experiential means. They experience the life that adults produce, through products geared at kids and general products they have access to. In the worst of scenarios children suffer indignities at the hands of adults and other children. As an educator, I believe it is paramount that I approach children in a realistic way. Acknowledging that they have experiences that are painful, real and substantial, just like adults. In some cases living around contemporary pop culture that is heavily saturated with media and entertainment sources can be harmful. Sources like these can speed up a child’s awareness and maturation beyond their developmental years. They may not be equipped to navigate clearly with reason and rationale those experiences and impressions. The inability of understanding and in dealing with these issues for children are not driven by “falsetto” innocence, these inadequacies are fueled by their innocence lost. To me, my job is to meet the child’s educational, developmental, emotional and social needs through professional practice. I don’t concretely mandate that they should achieve a certain level of maturation or even artistic skill by a certain age or grade level. They are organic individuals developing uniquely. To note, even Einstein was not well respected by teachers and peers early on in his college and professional life. For me, I am an encourager, a protector, a cheerleader, a mentor and someone who invests their time into the child, teaching them to invest time into themselves. The discoveries in art and the integration of the curriculum are really superseded by the need of the child to develop in a healthy way. My goal is to help this by being personable, professional and as Dr. Martin Luther King said, valued on the content of my character. I say that living in the classroom is essential, teaching art is peripheral. When we look at children as valuable people, then the bridge to learning can begin. I offer a sympathetic ear to students and their life experiences. I try to be positive, letting them make their own decisions and I encourage them to see life as an opportunity, though with realistic challenges. I also point them to look at existence through the artistic lens educationally and relatively. If dealing with a, behavioral, moral or integral life issue, I try and help them make positive decisions that demonstrate respect for themselves and others, while keeping their freedom of choice. I use comedy as a means for living and teaching and even point out the purpose of doing so. Doing this may offer strategies to cope and enjoy moments in this life. I try to be realistic, they know I make mistakes, and they know as a human being I can understand the commonalities of frustration, failure, pain, joy, success and life. This helps them to know I am a real person and we share similar experiences and emotions. I practice empathy and hope that they will develop ways to do so too. To do this goes well beyond art instruction and really defines me as a teacher and a member of our campus community and a human being. Duncum, P. (2002). Children never were what they were: Perspectives on childhood. In Contemporary issues in art education (pp. 97-107). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. |

Scott HughesArt Educator, Professional Photographer, Journalist. Alumni: Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed